Crossroads Crises in Perspective (Part 4) – Peak Energies in the Spotlight

**

This series of essays contains readings of reports, articles, and presentations that are in the public domain, with provided references. Readers are encouraged to approach the text with critical yet open minds.

**

Introduction

The crossroads that the world has arrived at is a transition from expansion to contraction on several levels, which is why a lot of emphases is placed on decentralisation in this series. Few people are aware that decentralisation will become increasingly important in the coming years, while global solutions presently on offer are typically geared toward further expansion and centralisation.

A shift from a centralised to a decentralised paradigm will be facilitated by metaphysical cyclic shifts, as well as constraints on some of the natural resources that are required for further unlimited global growth and expansion. Consequently, human populations will be challenged with many adjustments and even turnarounds, ultimately resulting in a return to a more natural order.

This chapter explores the world’s energy and mineral dependencies and probes whether industrialised civilisations could comprehensively transition away from fossil fuels. The implications of a peak oil scenario are explored with geopolitical developments placed within this context. The importance of fossil fuels in terms of what they do for us is a necessary starting point.

Our Energy Dependencies

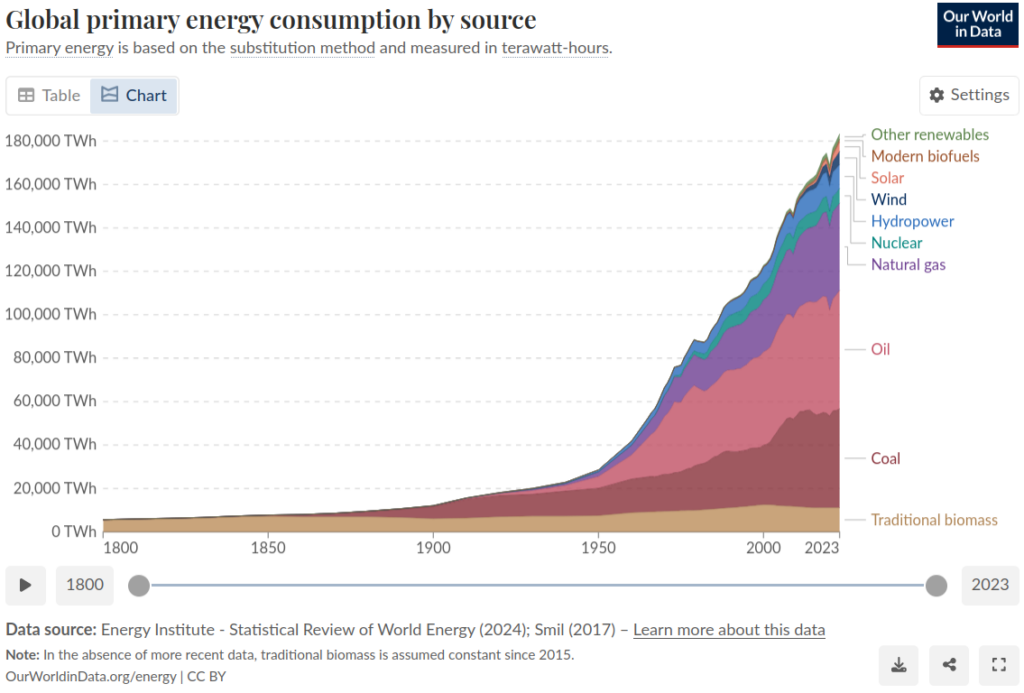

Fig. 1 – Global Primary Energy Consumption by Source – Our World in Data [source] 1

All industrial economies are dependent on fossil fuels for their economic growth. In our modern world, all humans greatly benefit from fossil fuels in numerous invisible ways. The only exceptions to that rule are people situated in faraway rural areas or regions where modernity is mostly lacking. In some cases, modern people choose to live their lives as organically as possible, but that is rare.

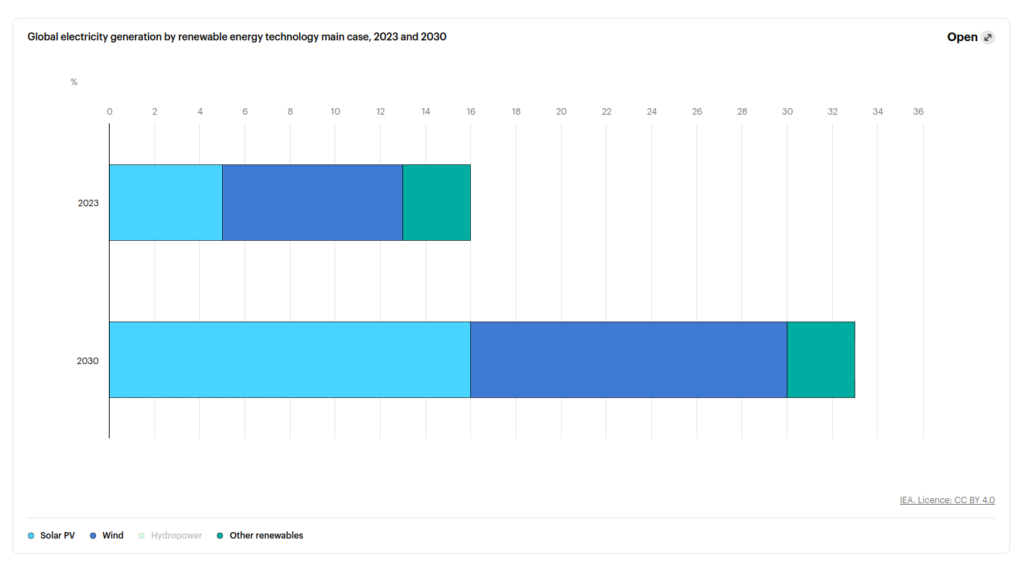

Notwithstanding the global energy transition that is underway, our modern industrial civilisation remains predominantly fossil fuel-based. Recent energy analyses have shown that renewable energy production consisting primarily of solar and wind power (excluding hydropower) constitutes only a fraction of global energy production at a mere 16% by 2023, according to a 2024 2 IEA report.

Fig. 2 – Global Electricity Generation by Renewable Technology Main Case, 2023 and 2030 [source] 2

It is estimated that by 2030, fossil fuels will still provide as much as 75% 2 of energy supplies to meet global demand, notwithstanding expected growth in the renewable energies sector. Interestingly, oil consumption and coal production hit record highs in 2023, with fossil fuels providing 81.5% of total primary energy 3, 4 consumption. Furthermore, it is believed that renewable energies are not growing fast enough to displace fossil fuels due to the accelerating demands for oil, natural gas, and coal.

Energy and the Economy

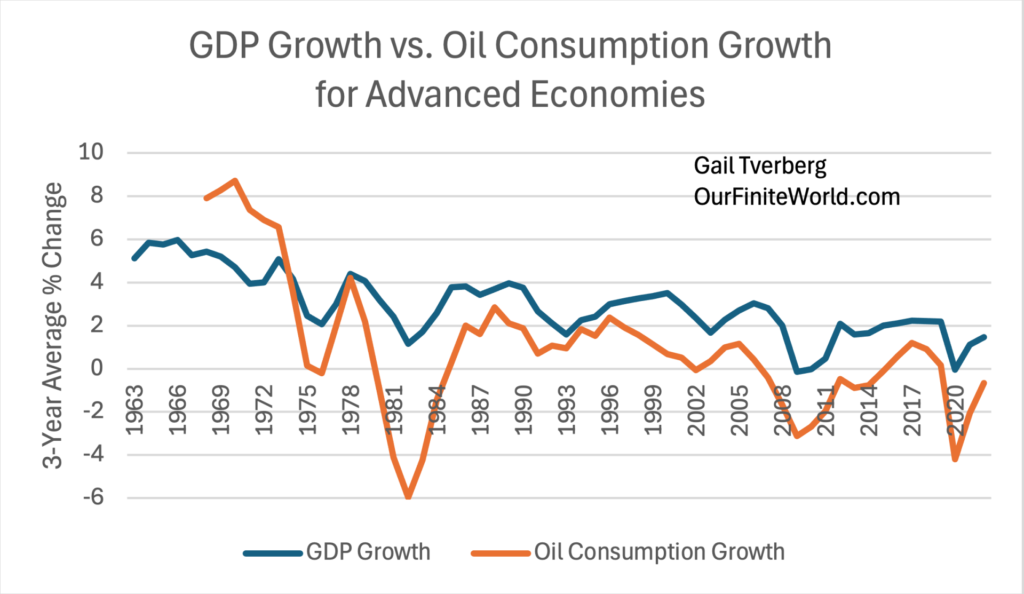

Easily attainable, low-cost, liquid fossil fuels are indispensable for economic growth because fossil fuels underpin modern economic growth. Unknown to many is that energy and the economy are inextricably linked, with GDP typically rising and falling 5 in relation to the volume of fossil fuels consumed.

Fig. 3 – Oil Consumption Growth vs GDP Growth of Advanced Economies – by Gail Tverberg [source] 5

Should global liquid fossil fuel production and distribution become seriously constrained, global economic growth would be negatively impacted as global energy markets are, to a large extent, centrally managed and coordinated. In a nutshell, the economies of the world are much less resilient today than they would otherwise have been if they had remained more decentralised.

Unlike environmental, climate and population crises, which could be managed locally or regionally (as discussed in A Crisis in Thinking and The Way Out), a serious energy crisis as a result of severe constraints on liquid fossil fuel supplies could be expected to impact virtually all economies due to international fossil fuel energy dependencies.

Periodic Energy Interruptions

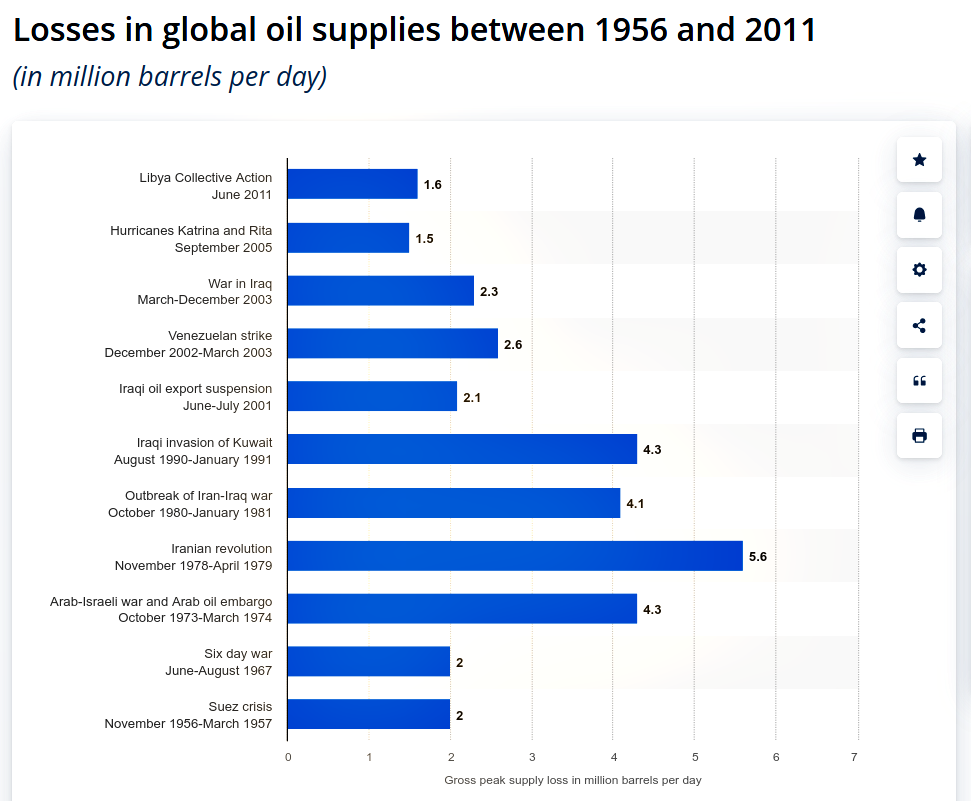

The economic growth paradigm, with its wealth-generating capacities and modern-day conveniences, is a very much taken-for-granted one. Due to the relative infrequency of global oil supply interruptions, the precariousness of stable oil supplies is not commonly well understood or often reflected upon.

Fig. 4 – Losses in Global Oil Supplies between 1956 and 2011 [source] 6

Although wide-scale interruptions in oil and gas supplies have historically been relatively few and far between, they had far-reaching consequences. Examples were the Arab-Israeli war and Arab oil embargo (1973-1974), the Iranian Revolution (1978-1979), Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait (1990-1991) and the Iran-Iraq war (1980-1981). 6

More recently, constraints in natural gas supplies from the Russian Federation into Europe have severely impacted energy prices in the EU since the Russo-Ukrainian war commenced in February 2022. It remains an open question of whether Europe would be able to adequately substitute gas supplies from Russia 7-9, considering that natural gas deliveries were completely suspended (after reduced flows since 2022) on the 1st of January 2025 10.

An Easy Enemy

Thinking of fossil fuels as an enemy or even as the enemy is a common reaction among activists, but as already established in prior essays, carbon dioxide levels are at the low end of the historical spectrum 11, 12 when viewing long-term historical trends, placing an important question mark behind claims that CO2 emissions pose an imminent threat to humanity.

If fossil fuels should make way for alternative energies, the latter should ideally be less damaging to the natural environment, not more so, considering that it is the harmful impacts of fossil fuels that are highlighted as the main reason for having to switch over to “clean” or “green” energy solutions. However, the practical reality is that renewable energies are only less obviously harmful to the natural environment, but not less so in practice – when implemented at scale on a long-term basis.

As previously argued (in Truth and Energy at the Crossroads), cross-sector economic interests in the green economy contribute to blind spots with regard to the negative environmental impacts of the energy transition itself. Said differently, green-washing the not-so-green energy transition while not noticing the green-washing has become the norm.

Introducing Peak Oil

Many policymakers, industry leaders, politicians, think tanks, thought leaders and innovators suffer from what is known as energy blindness to varying degrees, highlighting that independent research is required on the subject of peak oil, which necessitates weighing up analyses from a range of perspectives.

Peak oil predictions are typically regarded with scepticism by the general public since the notion of human prosperity declining at some point is often interpreted as either being conspiratorial or as an attack on people’s way of life.

Such scepticism is particularly noticeable within alternative media circles. For this reason, the subject of peak oil is given special attention in this chapter to arrive at solid answers about whether peak oil is real – or not.

Background Understanding

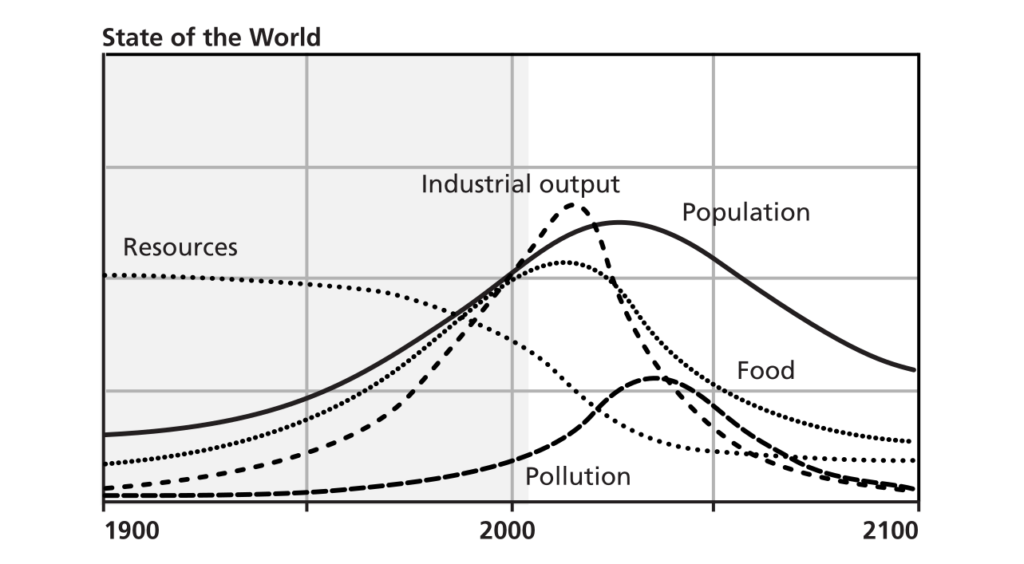

Fig. 5 – Limits to Growth – World 3 Scenario 1 [2004] based on Standard Run Scenario [1972] 13

Reports have been emerging since the 1970s that the world would one day face resource limits. The most prominent was “The Limits to Growth” (LTG) in 1972 14, commissioned by the Club of Rome. In that report, it was estimated that peak oil would unfold sometime during the mid-2020s, more or less from 2025 onward (according to a 2004 13 update based on the first edition of LTG 14). A general decline was expected to follow, lasting many decades.

Notwithstanding peak oil scepticism, periodic follow-up analyses have indicated that LTG reports had indeed been relatively accurate in some of their future modelling, especially in relation to a future decline of conventional liquid fossil fuels. Today, it can be observed that real-world trends have correlated relatively well with some of the LTG modelling (compare, for example, Fig. 5 and Fig. 6).

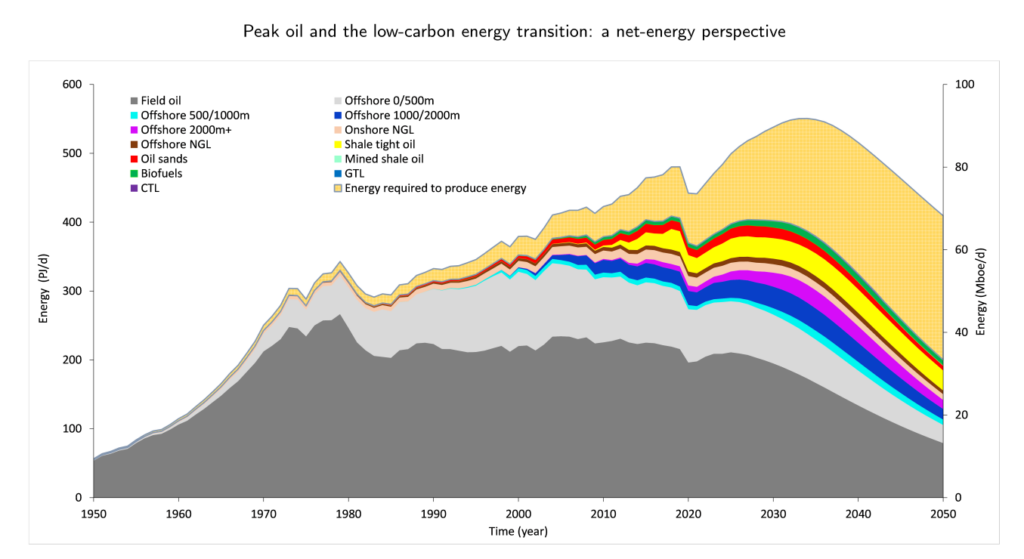

Fig. 6 – Average Oil Liquids Net-energy Production from 1950 to 2050, Compared to the Gross Energy [source] 15

A report of 2021 15, which evaluated a number of follow-up reports to the LTG, stated it as follows:

Our society can be described as a thermodynamic system that profoundly relies on abundant cheap energy sources such as petroleum to thrive. However, the rapid growth in the use of this non-renewable fossil fuel has undermined its future availability, leaving little doubt that an all-oil liquids peak will take place in the next 10 to 15 years. – Delannoy et al. (Peak Oil and the Low-carbon Energy Transition: A Net-energy Perspective – 2021) 15

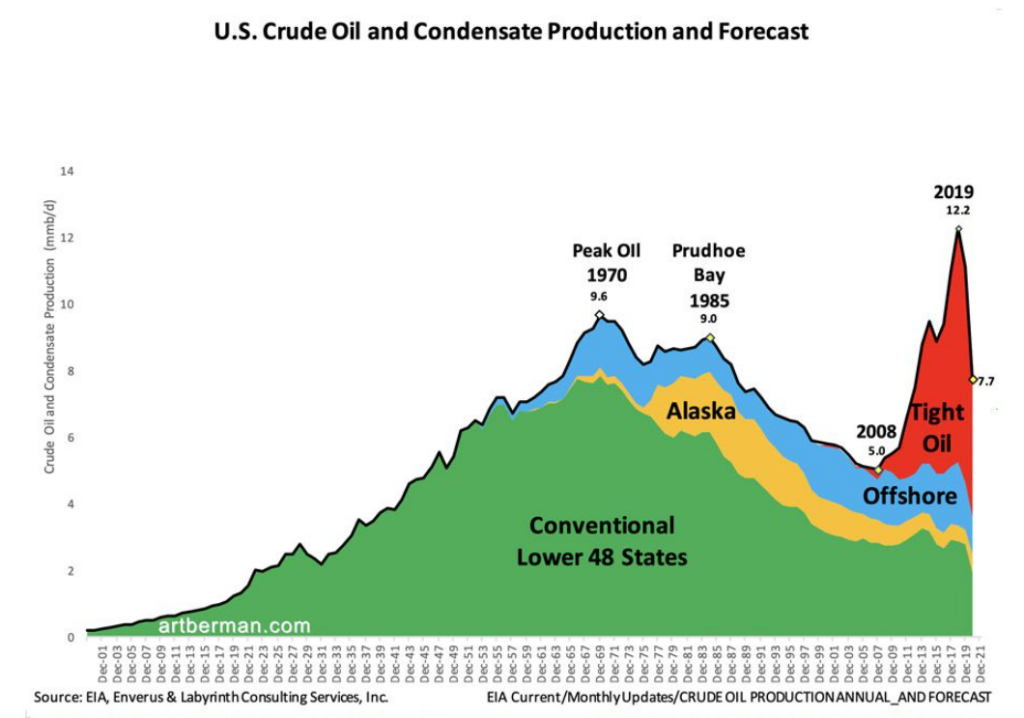

Other analyses from books and reports by industry experts 20, 21 estimated that peak oil had already occurred in 2005. Developments in the fracking and tar sands sectors subsequently provided for an interim recovery period (observe the red spike in the chart below) that extended the abundance of affordable liquid fossil fuels by at least another decade and a half 16, 18 (see: Fig. 7 and Fig. 8).

Fig. 7 – US Crude Oil and Condensate Production and Forecast – by Art Berman [source] 16

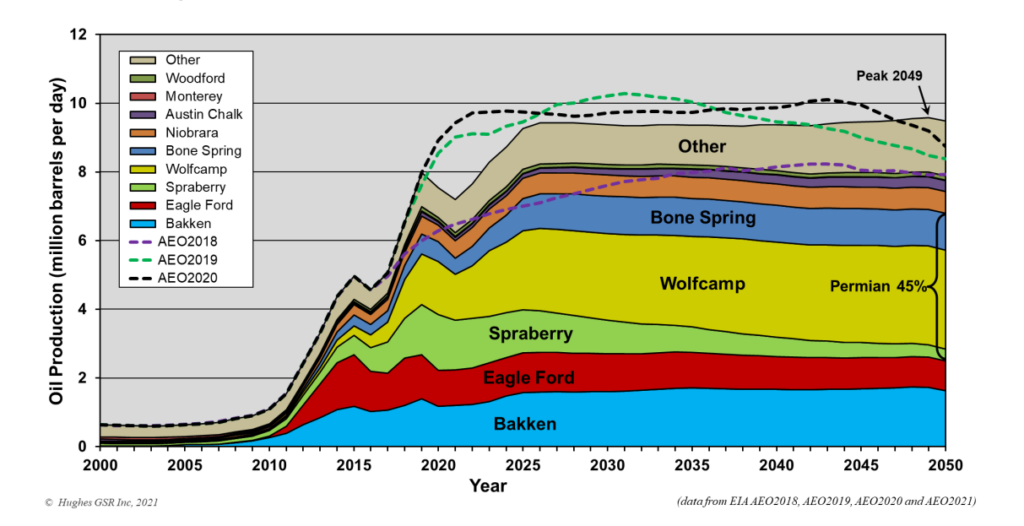

Although there are expectations that fracking operations for shale oil (tight oil) will continue to supplement crude oil production, it is estimated that the production of these resources will stagnate, too. While forecasts vary (and are sometimes adjusted), the general prognosis 18 is that of a long-term shale oil plateau, with declines expected in the years and decades to come (see Fig. 8).

Fig. 8 – US Tight Oil Production by Play in 2021 Forecast Compared to Earlier Forecasts [source] 18

Some of the factors at work are that returns on investments tend to decline sharply with shale oil operations after new capital-intensive wells are drilled. In short, due to a lack of significant growth in sections of the fracking sector, shale/tight oil would not adequately compensate for crude oil declines (for the entire world). The outlook for Canadian oil sands (i.e. tar sands) is similar, or worse 19, compared to shale oil.

Recurring Peak Oil

This brings the discussion to when peak oil is expected to happen again, and credible independent experts 20, 21 in the energy and mining sectors have concluded that peak oil had occurred (for a second time after 2005) between the years 2016 and 2020. The years 2017, 2018 and 2019 are alternatively pinpointed as when energy production started to reach a supply plateau.

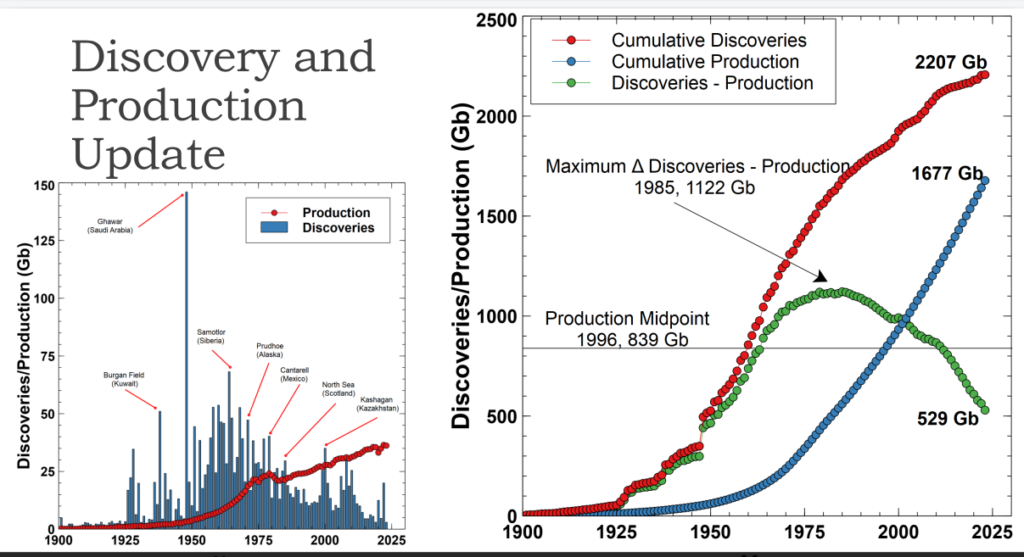

Globally, new oil discoveries have fallen for 6 years, with consumption of oil six times greater than discoveries from 2013 through 2019. In the US, conventional oil and gas discoveries from 2016 to mid-2020 were at their lowest levels for 70 years. – Alice J. Friedemann (Life After Fossil Fuels: A Reality Check on Alternative Energy – 2021) 20

Peak oil discovery was in 1962, and since then, rates of resource discovery have been declining persistently. New discoveries are limited: the exploration success rate in 2017 was a record low of 5%, and the average discovery size was 24mbbls. A projected range for the average decline rate on post-peak production is 5-7%, equivalent to around 3-4.5mb/d of lost production every year. – Simon P. Michaux (Oil from a Critical Raw Material Perspective – 2019) 21

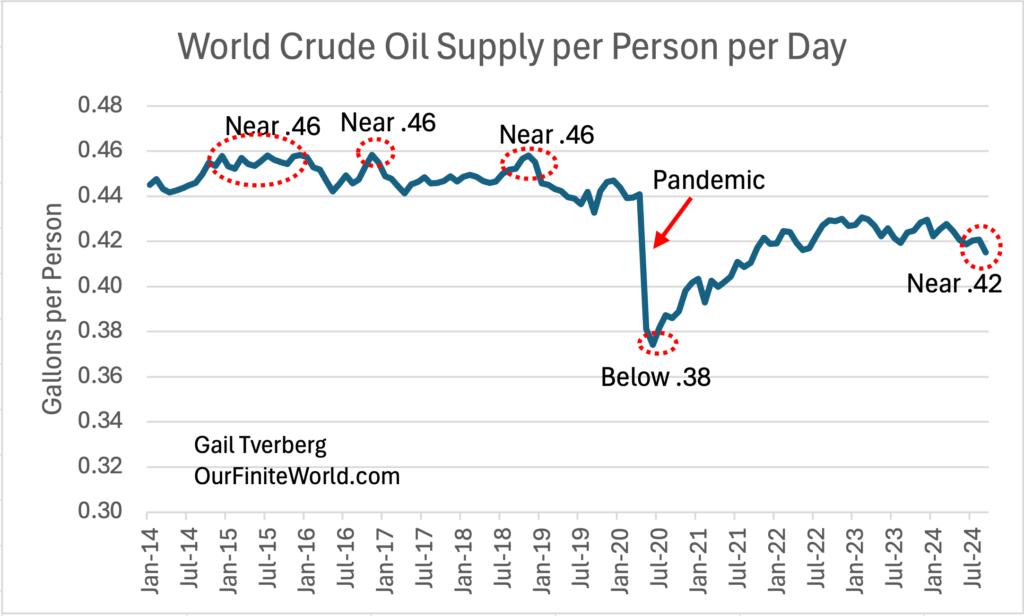

An important distinction to be aware of is the difference between oil discoveries versus oil production. While new oil discoveries have declined for several years, oil production has continued to rise as demand has increased because of economic growth and increasing population numbers. A noticeable exception was during the COVID-19 era when there was a significant decline in oil supplies per person 22 (see Fig. 9).

Fig. 9 – World Crude Oil Supply Per Person Per Day – by Gail Tverberg [source] 22

Should demand and consumption continue to outstrip new discoveries and production 16 (see Fig. 10 below), the potential consequences should become relatively clear considering the number of products made from oil and the number of industrial processes dependent on them (discussed in more detail further down).

Fig. 10 – Discovery and Production Update [source] 16

The midpoint of production happened in 1992, so half of all oil consumed occurred in the last 28 years. The maximum difference between discoveries and production was 1183 Gb in 1985. Oil is a finite resource, but we’ve been outstripping the rate of discoveries for 40 years. The difference between production and discoveries is a rapidly growing gap. – John Peach (The Growing Gap) 16

When zooming out to view discoveries versus production 16 (see left chart in Fig. 10), the picture of potential energy shortfalls in a decade or two becomes obvious. Although oil supplies to the market have almost recovered to pre-pandemic levels 22, 17 (see Fig. 9), they have not yet fully recovered (see also charts on this page 17 ).

The overall long-term outlook reflects future supply constraints as oil production is expected to continuously outpace oil discoveries as demand for oil increases with economic expansion and population growth (despite declining birth rates). Consequently, sooner or later, inflection points are bound to be reached.

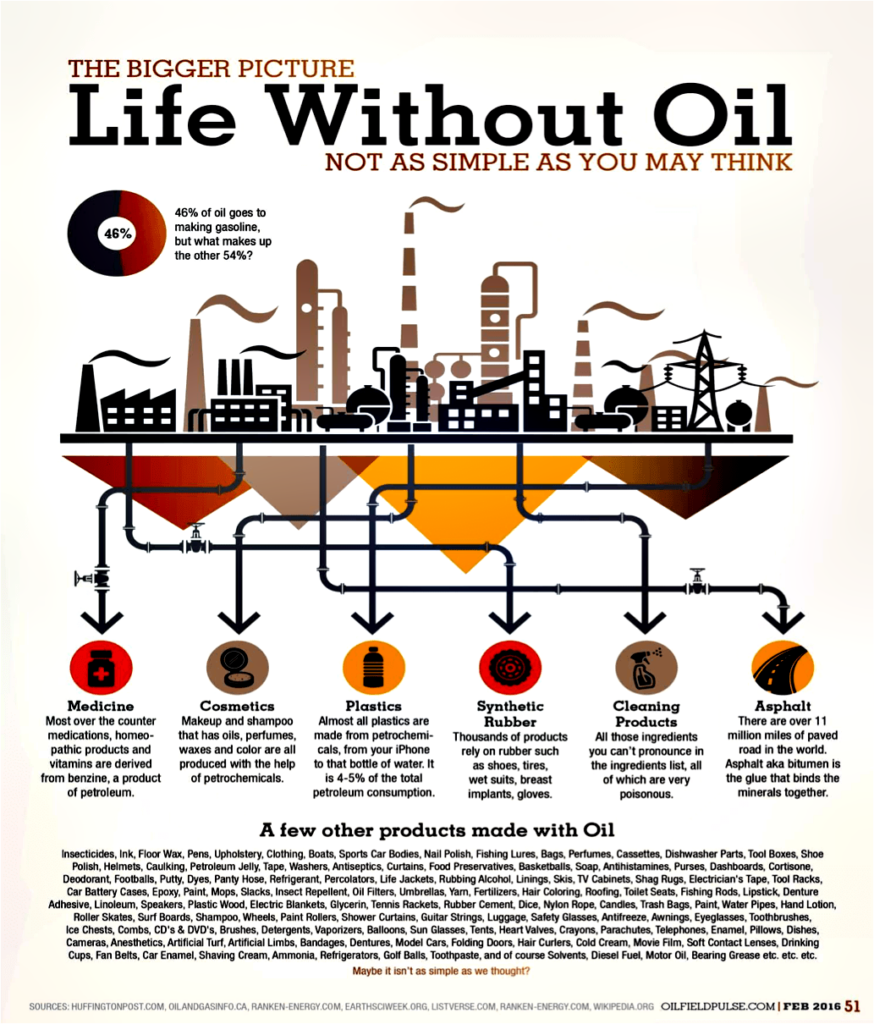

Products Made from Oil

Few people are familiar with just how many products are made from oil 23. Hydrocarbons are required in the manufacturing processes of a plethora of items and substances, including (but not limited to) medicines, plastics, paints, cleaning products, asphalt, insecticides, clothes, soap, cosmetics, deodorants, refrigerants, fertilisers, tyres, tents, gasoline, diesel fuel and motor oil (see also Fig. 11).

Fig. 11 – Life Without Oil – Not as Simple as You Think [click to enlarge] 23

As things stand, oil and coal cannot be replaced in the manufacturing processes of the vast majority of industrial items and products, which is unlikely to change in the foreseeable future. Conclusions circle back to the fact that since hydrocarbons and coal have so many byproducts that the industrialised, modern world is dependent upon, the world as we know it will not function normally without them.

Peak Oil’s Groundhog Day

As illustrated earlier, the reality is that peak oil is a recurring phenomenon. Evidence shows that this trend is repeating at an increased pace. When peak oil is reached, new discoveries or alternative extraction methods would typically resolve the issue temporarily, but peak oil would return a few years later. A logical deduction is that when peak oil becomes a constant, it is bound to overshadow all other perceived global crises, resulting in a reordering of priorities.

Energy Return on Investment (EROI)

A factor that industry experts are aware of is that although a lot of oil remains in the ground, the most easily accessible and highest quality oils have already been extracted. More expensive extraction methods that are yet to be fully developed would be required to access deeper, more difficult-to-reach oil deposits.

On the above point, the life cycle of a normal oil well could be understood within the concept of Energy Return On Investment, known as EROI 24. At first, it is affordable and profitable to extract the highest quality oil from a well, but as the quality diminishes, it becomes more cost-intensive to drill deeper until a break-even point is reached after which it is not profitable anymore.

With oil deposits that are very deep from the outset, the EROI 24 would be too low to begin with. Lower profit margins from the extraction operations combined with higher costs for the type of infrastructure required would render it uneconomical and not viable. Since the oil sector is already highly subsidised by governments, additional subsidies impacting national debt burdens could become unsustainable or untenable.

End of an Era

All things considered, the prospect of averting peak cheap oil is increasingly improbable. Rising food, fuel, and energy costs will necessitate frugality and lifestyle adjustments. The sobering reality is that the world has entered the end of an era.

We were fortunate enough to have been born into a time of wide-scale prosperity such as the world has never seen in history, but this recent era of abundance has only been possible because of cheap energy generated from easily obtainable oil, coal and natural gas.

Future Scenario Planning

When consulting sources related to future scenario planning, the following conclusions can be reached: Advance knowledge on the part of decision-makers with regard to future declines in fossil fuels (estimated to happen between the years 2020 and 2030, according to the LTG reports), combined with uncertainty about whether unconventional oils would adequately replace fossil fuels, played an important role in the planning of an energy transition ahead of time.

Shifting the world into a renewable energy paradigm based on minerals as a foundation with an interconnected economic growth paradigm (i.e. the green economy) appears to have been the preferred choice of action, which was envisioned decades ago as a solution for a future global peak oil scenario. This was evidently preceded by early global thinking 25-27 and comprehensive future scenario planning 28-31 after “The Limits to Growth” 14 was published, followed by numerous follow-up reports and books inspired by it.

Peak Oil: “The Final Verdict”

The trends covered in this essay have shown that some of the models presented in the 1972 (“normal run scenario”) 14 and 2004 (“future state” model 13) LTG reports were broadly correct in their analysis. As illustrated, real-world industry trends have, since the 1970s, correlated quite well in general with LTG forecasts as far as conventional liquid fossil fuels are concerned. Moreover, it seems that unconventional oils and minerals appear to show similar trends, although at a slower pace.

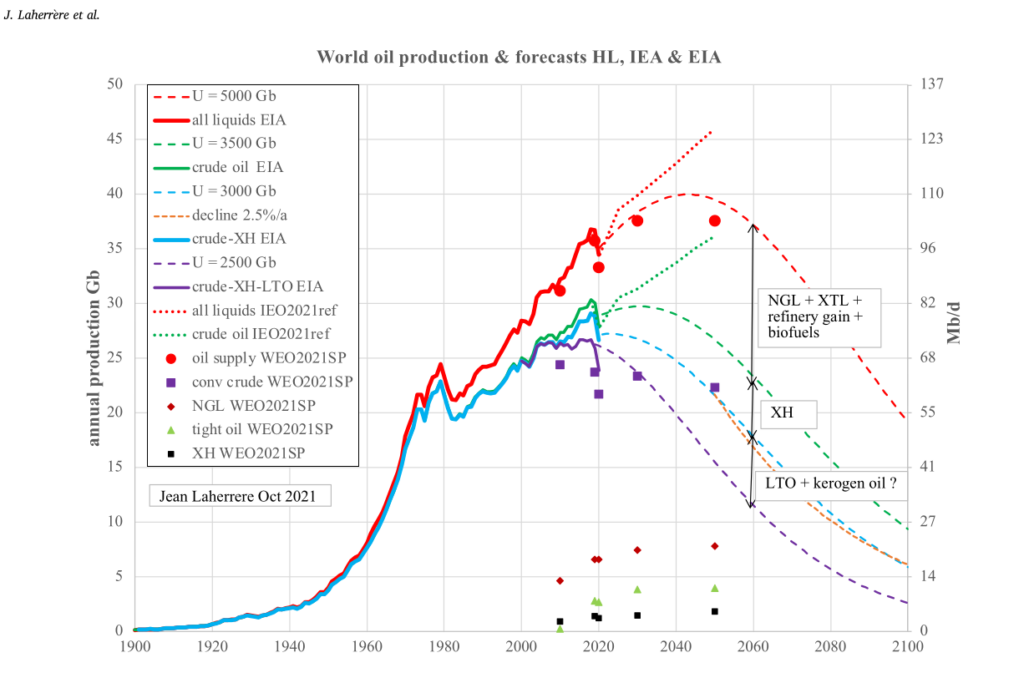

A research paper of 2022 titled “How much oil remains for the world to produce? Comparing assessment methods, and separating fact from fiction” 32 by Jean Laherrère et al. sums up what could be considered a final verdict (as far as research for this project is concerned) on the pressing questions of (1) whether peak oil is real and (2) when it would become a constant.

If we add to conventional oil production that of light-tight (‘fracked’) oil, our analysis suggests that the corresponding resource-limited production peak will occur soon, between perhaps 2022 to 2025. If then we add tar sands and Orinoco oil, the expected resource-limited total peak occurs around 2030. However, there is a major question over whether significantly increased production rates of the latter two classes of oil are possible. Finally, the resource-limited production peak of global ‘all-liquids’ is expected about 2040 or a bit after if the latter liquids are also produced at the maximal rate. – J. Laherrère et al. (How much oil remains for the world to produce? Comparing assessment methods and separating fact from fiction – 2022) 32

Fig. 12 – World Oil Production and Forecasts HL, IEA, EIA [source] 32

Abiotic Oil

An interesting phenomenon within alternative media is that some writers embrace a belief that abiotic oil 33 would provide solutions for an energy crisis and that the concept of peak oil is a false construct. However, credible and comprehensive resources factually supporting such beliefs are never produced on request after pundits make those claims.

Doing independent research on the subject does not yield many results either. While abiotic oils may provide future solutions when new technologies become available to access them, there seems to be no clear evidence (when reading the opinions of industry experts on the subject 33 ) that abiotic oil would provide viable solutions in the short or the near term.

Unknown Unknowns

The Hubbert Curve is a method for predicting the likely production rate of any finite resource over time. When plotted on a chart, the result resembles a symmetrical bell-shaped curve. The theory was developed in the 1950s to describe the production cycle of fossil fuels. However, it is now considered to be an accurate model for the production cycle of any finite resource. – Hubbert Curve (Investopedia) 34

It is worth bearing in mind that there are always unknown unknowns 35. Some analysts are of the view that the Hubbert Curve 34 method that is used for peak oil modelling lacks accuracy because it fails to take certain issues into account 36, such as future technological advances or unexpected geopolitical disruptions.

That being the case, the same may be said about any type of future modelling, meaning that unforeseen circumstances would always be part of future reality – not everything can be anticipated – which is why any frameworks that are used for forecasting should always be viewed as conceptual mechanisms that have limitations.

For example, when the first LTG reports were released, the shale oil revolution, as well as oil extraction from Canadian tar sands were unknown unknowns 35 at the time. However, these unconventional oils have only provided a temporary respite from peak oil returning. Long-term peak oil is still set to happen in the immediate decades ahead of us.

Abiotic oil could – hypothetically speaking – have provided another reprieve, but that did not happen. Always hoping that unknown unknowns would come to the rescue in the form of “lucky breaks” is not a sound strategy.

Implications of Peak Oil

Given the societal dependence on oil and the difficulties in achieving a transition to low-carbon energies in time, such a peak is likely to have deep consequences that are not yet fully understood and which might handicap the transition itself. – Delannoy et al. (Peak Oil and the Low-carbon Energy Transition: A Net-energy Perspective – 2021) 15

Since virtually all modern systems are underpinned by fossil fuels (industrial food production and modern transport systems being important examples), maintaining globalisation at the same level by using alternative energies will not be feasible since renewable energies are not capable of replicating the energy output (due to differences in energy densities) of liquid fossil fuels or coal (another factor well-known by industry experts).

A complete or total energy transition away from fossil fuels and hydrocarbons is, therefore, simply not technically possible. At the same time, nuclear energy has limitations, too, since it is primarily used for electricity generation. Lubricants and other important byproducts from oil, gas and coal cannot be produced by nuclear energy, solar power, wind energy, or hydroelectric schemes.

The current system was built with the support of the highest calorifically dense source of energy the world has ever known (oil), in cheap, abundant quantities, with easily available credit and seemingly unlimited mineral resources. – Simon P. Michaux (Assessment of the Extra Capacity Required of Alternative Energy Electrical Power Systems to Completely Replace Fossil Fuels – 2021) 37

The most probable real-world outcome would be that a range of alternative and renewable energies would continue to supplement conventional oil production but would not fully replace it, while a general plateau and subsequent decline could be expected to unfold in the next 50 years. In other words, looking at the issue of peak oil from various perspectives yields similar conclusions.

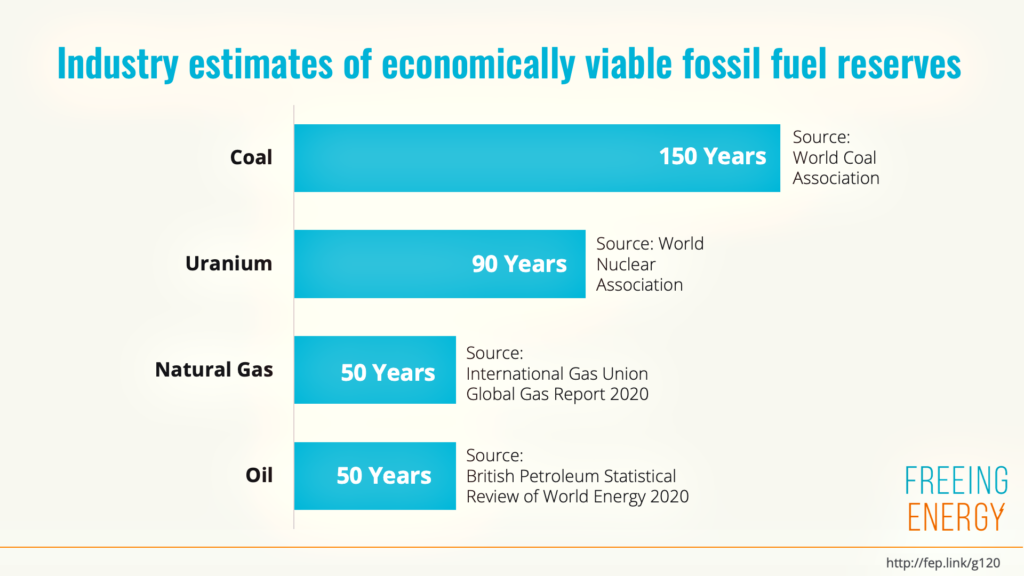

Fig. 13 – Industry Estimates of Economically Viable Fossil Fuel Reserves [source] 38

Oil and coal are unlikely ever to be phased out entirely, notwithstanding global campaigns or policies to that effect. As the declines of liquid fossil fuels deepen, most countries would probably revert to coal (there are more coal reserves left than oil 38) and expand their nuclear power generation capacities (there is still sufficient uranium left too 38) while countries lacking nuclear power are likely to add it to their overall energy-mix.

Reinforced Dependencies

To recap a point made before (in the previous chapter), there’s significant irony in the fact that the world’s fossil fuel dependencies are being reinforced by the introduction of renewable energy devices and installations. These items and infrastructure cannot be produced or installed without fossil fuels. Furthermore, they need to be replaced periodically, which is why they are referred to as “replaceables” in some energy discussion groups.

The Energy Expansion

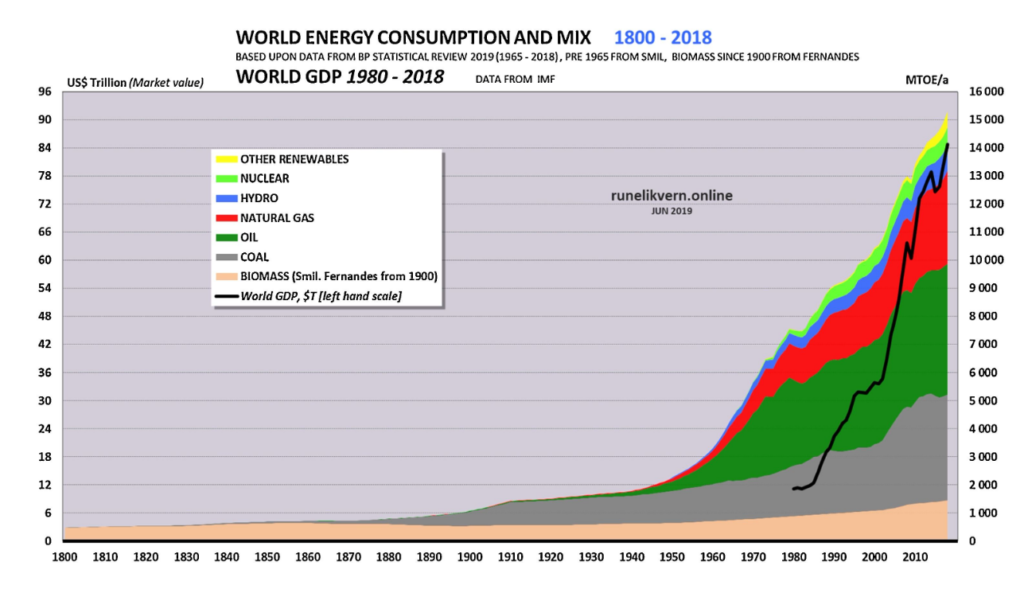

The practical outcomes of the energy transition reveal that an introduction of alternative energies typically results in an expansion of energy production into additional methods of production, rather than resulting in a transition away from fossil fuels. This has been confirmed by an analysis illustrating a big-picture view of energy consumption over the last 200-plus years, from 1800 to 2018 (see Fig. 14).

Fig. 14 – World Energy Consumption and Mix 1800 to 2018 – by Runelik Vern [source] 16

A plot of energy consumption over the period 1800-2018 shows that energy consumption of all types is generally increasing. We aren’t substituting one form of energy for another: we’re just adding more energy from all sources to the mix. – John Peach (The Growing Gap) 16

The trend clearly shows how world GDP has risen over the decades as a result of ever-increasing energy consumption. A cause-and-effect deduction (and it is worth pausing on this factor for a moment) is that when energy production and supplies reach a plateau, so would world GDP. After a period of stagnation, a decline in world GDP could be anticipated should no other compensatory growth strategies emerge (for which brainstorming essay contests 40 were launched in some zones, apparently).

In light of everything discussed so far, it would be fair to say that the use of primary fossil fuels such as oil and coal will continue indefinitely in the background. In contrast, the energy transition will continue to be promoted for commercial and economic reasons rather than for the environment. At the same time, the objective of having alternative energy generation capacities in place for softer landings when energy disruptions arrive would be met, too.

Whether intentional or not, “anti-oil” and “anti-coal” activism merely provide additional momentum by way of “moral causes” for an expansion into renewable energy production while masking that it is a diversification of the energy sector into a wider array of energy production methods and systems (within the overall energy landscape) that’s underway under the banner of a (so-called) green energy transition.

As an aside, one of the main reasons why less developed (yet resource-rich) nations are becoming more vulnerable to outside interventions is related to the fact that “minerals have become the new oil” (which is a phrase used by some people in the renewable energies sector 39).

Introducing Peak Minerals

An unknown reality is that the world will not only be arriving at peak oils but also at peak minerals. In-depth feasibility studies have shown that to accomplish a comprehensive transition away from an economy based on fossil fuels to one primarily based on minerals (for the production of renewable energy installations and technologies), enormous quantities of critical minerals would be required.

Research by experts in the mining and energy sectors has shown that there simply will not be sufficient key minerals to make a full energy transition. Consequently, a mineral-based industrial system would not be feasible at scale without the supplemental support of fossil fuels, and it would not be practicable beyond two or three generations (for details, please see referenced reports 37, 41).

The replacement needs to be done at a time when there is comparatively very expensive energy, a fragile finance system saturated in debt, not enough minerals, and an unprecedented world population embedded in a deteriorating natural environment. – Simon P. Michaux (Assessment of the Extra Capacity Required of Alternative Energy Electrical Power Systems to Completely Replace Fossil Fuels – 2021) 37

These realities have been highlighted extensively by associate professor Simon Michaux of the GTK Institute in Finland. His work (several reports) makes for compelling reading as it provides a fundamental understanding of the serious mineral limits that the world will be facing in the not-too-distant future. Other experts have come to similar conclusions, notably Mr Mark Mills from the Skagen Foundation in Norway. 41

Healthy debates (in the form of video presentations, interviews and conferences) about all these factors can be found online, and readers are encouraged to familiarise themselves with the results of the reports mentioned. Being aware of the real-world limitations of making a full transition into a mineral-based energy paradigm consisting of solar panels, wind turbines, and electric cars is essential. Conclusions point to the fact that peak minerals (copper being a case in point) will almost certainly follow peak oil.

Since most people have major blind spots when it comes to the concept of peak oil, and because the concept of peak minerals is simply beyond their awareness, these looming challenges are unlikely to become widely known before shortages set in. Consequently, citizens will face the practical realities of peak oil and minerals in stops and starts as the years go by.

Contraction Economics

The industrial ecosystem is in the process of transitioning from growth-based economics to contraction-based economics. This will affect all sectors of the global ecosystem, all at the same time (in a 20-year window). We are there now and should respond accordingly. – Simon P. Michaux (The Mining of Minerals and the Limits to Growth – 2021) 42

People have a misimpression regarding how world peak oil can be expected to behave. The world economy has continued to grow, but now it is beginning to move in the direction of contraction due to an inadequate supply of crude oil. – Gail Tverberg (An energy and the economy forecast for 2025) 43

A decline in fossil fuels which would ultimately be beyond the control of humans, would mean the stagnation of economic growth in many sectors. As a result, growth economics is expected to turn into what has been described as contraction economics.

How that would unfold internationally remains unclear since not all economies, sectors or regions are the same, but as highlighted in another essay 44, the reality is that few people are prepared to willingly give up modernity, which is to be expected since we live in an era of hyper-materialism.

It must be acknowledged, though, that there is a growing number of people who “have seen the future” (and have seen the light) because they are sufficiently informed about peak oil (as well as peak minerals), allowing them to make the required mind-shifts in anticipation of an imminently changing paradigm. Many are actively pioneering solutions for localised self-sufficiency in line with authentic environmental consciousness.

Towards a More Natural Order

All the factors evaluated could lead one to realise that effective long-term solutions should ideally revolve around less urbanisation and modernisation and a return to a simpler way of life. However, the world is still travelling in the opposite direction with accelerated momentum, but evidence of significant turnarounds is already starting to appear in the first quarter of 2025 (related to the impacts of global tariffs imposed by the USA).

Considering our ultra-materialistic, consumer-driven world featuring industrialisation and globalisation powered by an abundance of affordable fossil fuels to date, there’s been no growth of a collective awareness or a universal consciousness that would lead populations toward early transitions away from excessive materialism towards more responsible and less extravagant lifestyles. It is up to individuals and small communities to lead the way, but as awareness of our predicament grows, more people will come on board. However, the changing energy landscape will inevitably necessitate adjustments.

This transition may prove psychologically challenging, especially for people who are committed to the belief that peak oil is a false construct. The evidence presented in this essay suggests the contrary, that peak oil is a very real phenomenon. Although not wanting to go back in time is a default position for most humans, history tends to rhyme, which, from a cyclic perspective, would revolve around reverting back to more classic ways of living.

A renewal and a return to a more natural order in which humans interact more symbiotically with nature and live more in harmony with it will, over time, be brought about by unavoidable energy realities which will be accompanied by mind-shifts related to a change in the spirit of the age (see also The Lights Along the Way).

Mind-Shifts, Off-ramps and Exit Strategies

By facing the truths of our energy predicaments, suitable exit strategies and off-ramps can be envisioned, but first, mind-shifts are required in terms of acknowledging the realities that we are facing. If renewable energies will not provide long-term solutions, and if it is almost certain that the world will undergo an energy decline, real solutions should logically revolve around decentralisation.

To recap once more, unlike environmental, population and climate crises, global constraints in fossil fuel supplies could result in a genuine worldwide energy crisis due to the volumes of oil that industrial economies require to function until such time that countries find their feet in terms of energy localisation, which will take time. In the interim, renewable energies can only provide partial or temporary solutions.

The Hierarchy of Crises

If a hierarchy of crises is to reflect crises ranked in terms of posing a threat to the basic functioning of societies, the order of the hierarchy will shift dramatically when the real-world consequences of peak oil and peak minerals make themselves felt.

The current global hierarchy of crises features a purported “climate crisis” at the top of the list because comfort zones allow people to be less discerning about which crises they think of as the most pressing.

Navigating the Challenges

Our current overly materialistic awareness of energy will, over time, give way naturally to a growing metaphysical energy awareness, and that will happen incrementally as the metaphysical energy seasons change. On a practical level the world is likely to face many challenges going forward in terms of having to adapt to a less resource intensive civilisation, simply because fossil fuels are dwindling (Cf. The Lights Along the Way) 45

The economic growth imperative demands our way of life within the context of a ubiquitous globalised consumer culture, which (truth be told) is a trap that few people really want to escape from. In a highly materialistic age material growth is automatically prioritised over spiritual growth, while the contrary is true during a spiritual age.

The consciousness of our present era is sorely lacking in spirituality because we are at the end of a large metaphysical cycle 45. The upside is that this epoch is finally drawing to a close, challenging us to prepare for navigating the upcoming changes courageously and purposefully by knowing what issues will have to be dealt with (some have been discussed in this essay).

In the future, authentic environmentalism will re-emerge when less materialistic mindsets flourish after humanity has passed through its adaption bottlenecks due to the repercussions of peak-fossil fuels followed by peak minerals. Localisation strategies that place people in closer proximity to nature would once again foster genuine care for the environment through more authentic engagement with it.

Towards Decentralisation

The concept of there being limits to material and economic growth depends on whether local or national resources are considered in isolation, or whether they are analysed within a global context. The picture changes dramatically when the focus is shifted to local growth by decoupling from mindsets that are dominated by global growth considerations.

All regions are resource-rich in their own particular ways while being resource-poor in other respects, but globalisation has masked these particularities and disparities. Unique local strategies tailored to local circumstances may pave the way for a variety of localised solutions in the face of a global economic growth crisis as a result of resource constraints in the fossil fuel sectors.

Although there’s still significant momentum behind mass centralisation (as a consequence of globalism and globalisation), it can be observed that sentiments are starting to shift towards decentralised solutions as they are clearly more logical and practical in the face of a number of crises related to the globalised nature of supply chains and due to growing conflicts in energy-rich regions.

Recalibration Required

The writer would suggest that in preparing for a changing paradigm, a recalibration in thinking is required in how crises are prioritised. The following adjustments may be considered in the process:

-

Acknowledging our fossil fuels dependencies.

-

Acknowledging peak oil.

-

Acknowledging that renewable energies have serious limitations.

-

Acknowledging the destructive impacts of renewable energies on the environment.

-

Acknowledging that shortages in key minerals will limit the energy transition.

-

Acknowledging that lifestyle adjustments will be required despite the energy transition.

-

Admitting that climate change is not the most pressing problem facing humanity.

-

Shifting mindsets to local growth strategies decoupled from global growth solutions.

-

Returning to an authentic environmental consciousness.

-

Developing and prioritising spiritual growth strategies for psychological resilience.

To be continued…

By J.J. Montagnier

Published: May 9th, 2025 at GypsyCafe.org

Related article: Going Beyond Limits to Growth

Please note that using selected quotes and citations does not imply that the writer supports the entire worldviews of the persons cited or the conclusions contained in the referenced materials. The approach is to identify valuable pieces of information and isolate important facts for independent analysis through critical thought for fresh perspectives and a unique understanding of unfolding events.

J.J. Montagnier is an independent researcher and writer based in the Southern Hemisphere, at a midpoint between West and East. The views and opinions expressed are those of the writer. This content is provided for educational objectives as a public service and is not for commercial use.

Copyright © All Rights Reserved. GypsyCafe.org

References

References for further reading are a necessary complementary feature due to essays having limited scope and are carefully selected with the reader in mind.

1. Global direct primary energy consumption [Internet]. Our World in Data. [cited 2025 Mar 29]. Available from: https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/global-primary-energy

2. Executive summary – renewables 2024 – Analysis [Internet]. IEA. [cited 2025 Mar 29]. Available from: https://www.iea.org/reports/renewables-2024/executive-summary

3. Rapier R. 2024 World Energy Review – Record Fossil Fuel and Renewable Growth [Internet]. Shalemag.com. 2024 [cited 2025 Mar 29]. Available from: https://shalemag.com/2024-world-energy-review-record-fossil-fuel-and-renewable-growth/

4. Energy Institute. Home [Internet]. Statistical review of world energy. [cited 2025 Mar 29]. Available from: https://www.energyinst.org/statistical-review

5. Tverberg G. Oil-consumption-growth-vs.-GDP-growth-of-Advanced-Economies [Internet]. Our Finite World. 2024 [cited 2025 Mar 29]. Available from: https://ourfiniteworld.com/oil-consumption-growth-vs-gdp-growth-of-advanced-economies/

6. Disruptions to global oil supplies [Internet]. Statista. [cited 2025 Mar 29]. Available from: https://www.statista.com/statistics/192866/disruptions-to-global-oil-supplies-since-1957/

7. Psaropoulos JT. Europe imports more Russian gas, aiding wartime economy, report finds [Internet]. Al Jazeera. 2025 [cited 2025 Mar 29]. Available from: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2025/3/27/europe-imports-more-russian-gas-aiding-wartime-economy-report-finds

8. Perdana S, Vielle M, Schenckery M. European Economic impacts of cutting energy imports from Russia: A computable general equilibrium analysis. Energy Strat Rev [Internet]. 2022;44(101006):101006. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.esr.2022.101006

9. Pichler A, Hurt J, Reisch T, Stangl J, Thurner S. Economic impacts of a drastic gas supply shock and short-term mitigation strategies. J Econ Behav Organ [Internet]. 2024;227(106750):106750. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2024.106750

10. The End of Russian Gas Transit via Ukraine – Immediate Impact and Implications for the European Gas Market in 2025 [Internet]. Oxfordenergy.org. [cited 2025 Mar 29]. Available from: https://www.oxfordenergy.org/publications/the-end-of-russian-gas-transit-via-ukraine-immediate-impact-and-implications-for-the-european-gas-market-in-2025/

11. Fagan, R [Internet]. Global warming unpicked. Earth climate over geological time; [last updated 2023 March 26; cited 2024 May 17]. Available from: https://www.dr-robert-fagan.com/global-warming-unpicked/

12. Berner RA. GEOCARB II: A revised model of atmospheric CO 2 over Phanerozoic time. Am J Sci [Internet]. 1994 [cited 2024 May 17];294(1):56-91. Available from: https://typeset.io/papers/geocarb-iii-a-revised-model-of-atmospheric-co2-over-4jxmgwzkl6

13. Meadows DH, Randers J, Meadows DL. The Limits to Growth: The 30-year Update. 3rd ed. London, England: Earthscan; 2005.

14. Meadows DH, Meadows DL, Randers J, Behrens WW. The limits to growth: A report for the Club of Rome’s project on the predicament of mankind. Universe Books; 1972.

15. Delannoy, Louis & Longaretti, Pierre-Yves & Murphy, David & Prados, Emmanuel. (2021). Peak oil and the low-carbon energy transition: A net-energy perspective. Applied Energy. 304. 10.1016/j.apenergy.2021.117843. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/354885905_Peak_oil_and_the_low-carbon_energy_transition_A_net-energy_perspective

16. Peach J. The growing gap [Internet]. Wild Peaches. 2022 [cited 2025 Apr 4]. Available from: https://wildpeaches.xyz/blog/the-growing-gap/

17. Matt. US shale oil seems to cover up peaking crude oil production in the rest of the world since 2018 [Internet]. Crudeoilpeak.info. [cited 2025 Apr 4]. Available from: https://archive.today/2025.04.05-040847/https://crudeoilpeak.info/post-covid-crude-production-in-world-outside-the-us-still-lower-than-end-2018

18. Hughes D. Shale Reality Check 2021 [Internet]. Postcarbon.org. 2021 [cited 2025 Mar 29]. Available from: https://www.postcarbon.org/publications/shale-reality-check-2021/

19. Government of Canada, Canada Energy Regulator. CER – Canada’s energy future 2021 Fact Sheet: Oil sands [Internet]. Cer-rec.gc.ca. 2023 [cited 2025 Mar 30]. Available from: https://www.cer-rec.gc.ca/en/data-analysis/canada-energy-future/2021oilsands/index.html

20. Friedemann AJ. Life after fossil fuels: A reality check on alternative energy. 1st ed. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature; 2022.

21. Michaux, Simon. (2020). GTK Oil from a Critical Raw Material Perspective FINAL CC signatures. 10.13140/RG.2.2.16253.31203. Available from: https://tupa.gtk.fi/raportti/arkisto/70_2019.pdf

22. Tverberg G. An energy and the economy forecast for 2025 [Internet]. Our Finite World. 2025 [cited 2025 Apr 4]. Available from: https://ourfiniteworld.com/2025/01/05/an-energy-and-the-economy-forecast-for-2025/

23. Life Without Oil [Internet]. Tagoil.com. 2016 [cited 2025 Apr 5]. Available from: https://archive.today/2025.04.05-043153/https://web.archive.org/web/20171103214211/http://www.tagoil.com/life-without-oil/

24. Hayes A. Energy return on investment (EROI): Overview, calculations [Internet]. Investopedia. 2010 [cited 2025 Apr 13]. Available from: https://www.investopedia.com/terms/e/energy-return-on-investment.asp

25. Mesarovic M. Mankind at the turning point: The second report. Dutton Books; 1974.

26. [RIO] Reshaping the international order: A report to the Club of Rome. Dutton Books; 1976.

27. Morin. Homeland Earth. Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press; 1998.

28. Al Hammond Paul Raskin Rob Swart GG. Branch Points: Global Scenarios and Human Choice [Internet]. 1997 Jan. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/280528674_Branch_Points_Global_Scenarios_and_Human_Choice

29. Raskin PD. Bending the Curve: Toward Global Sustainability [Internet]. Polestar; 1998. Available from: https://tellus.org/tellus/publication/bending-the-curve-toward-global-sustainability/

30. Al Hammond Robert Kates Rob Swart. Great Transition: The Promise and Lure of the Times Ahead [Internet]. 2002. Available from: https://greattransition.org/gt-essay

31. Raskin P. Journey to Earthland [Internet]. Tellus Institute; 2016. Available from: https://greattransition.org/publication/journey-to-earthland

32. Laherrère J, Hall CAS, Bentley R. How much oil remains for the world to produce? Comparing assessment methods, and separating fact from fiction. Curr Res Environ Sustain [Internet]. 2022;4(100174):100174. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/362050842_How_much_oil_remains_for_the_world_to_produce_Comparing_assessment_methods_and_separating_fact_from_fiction

33. Anderson B. The “abiotic oil” controversy [Internet]. Resilience. Resilience.org; 2004 [cited 2025 Apr 6]. Available from: https://www.resilience.org/stories/2004-10-06/abiotic-oil-controversy/

34. Fernando J. Hubbert curve: What it is, how it works, example [Internet]. Investopedia. 2009 [cited 2025 Apr 6]. Available from: https://www.investopedia.com/terms/h/hubbert-curve.asp

35. Nordqvist C. What are unknown unknowns? Definition and examples [Internet]. Market Business News. 2018 [cited 2025 Apr 6]. Available from: https://marketbusinessnews.com/financial-glossary/financial-glossary-u__trashed/unknown-unknowns/

36. Hussein AA. Why Hubbert’s peak oil theory fails? [Internet]. Oil Industry Insight. 2015 [cited 2025 May 2]. Available from: https://web.archive.org/web/20211002195907/https://oilindustryinsight.com/oil-gas/insight-analysis/why-hubberts-peak-oil-theory-fails/

37. Michaux, Simon. (2021). Assessment of the Extra Capacity Required of Alternative Energy Electrical Power Systems to Completely Replace Fossil Fuels. 10.13140/RG.2.2.34895.00160. Available from: https://tupa.gtk.fi/raportti/arkisto/42_2021.pdf

38. Fossil fuel reserves will become unviable [Internet]. Freeing Energy. The Freeing Energy Project; 2020 [cited 2025 Apr 13]. Available from: https://www.freeingenergy.com/facts/fossil-fuel-reserves-will-become-unviable-g120/

39. The Energy Disruptors: UNITE Summit. Realizing a 300 TWh battery future. Simon Moores. EDU2022 [Internet]. YouTube; [cited 2025 Apr 6]. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=r-EO65iFKtM&pp=ygUcU2ltb24gTW9vcmVzIFJlYWxpemluZyBhIDMwMA%3D%3D

40. Today R. ‘The Future of the World: New Platform for Global Growth’ essay contest closes submissions [Internet]. RT. 2025 [cited 2025 Apr 18]. Available from: https://www.rt.com/russia/614496-future-of-world-new-platform/

41. Mills MP. The “new energy economy”: An exercise in magical thinking [Internet]. Manhattan Institute. 2019 [cited 2025 Apr 6]. Available from: https://manhattan.institute/article/the-new-energy-economy-an-exercise-in-magical-thinking

42. Michaux, Simon & Michaux, Simon. (2021). The Mining of Minerals and the Limits to Growth. 10.13140/RG.2.2.10175.84640. Available from: https://tupa.gtk.fi/raportti/arkisto/16_2021.pdf

43. Tverberg, G. (2025, January 6). An energy and the economy forecast for 2025. Our Finite World. https://ourfiniteworld.com/2025/01/05/an-energy-and-the-economy-forecast-for-2025/

44. Montagnier JJ. Going Beyond Limits to Growth [Internet]. Energy Shifts. 2018 [cited 2025 Apr 6]. Available from: https://energyshifts.net/there-are-no-limits-to-growth/

45. Montagnier JJ. The Lights Along the Way [Internet]. Energy Shifts. 2021 [cited 2025 May 4]. Available from: https://energyshifts.net/the-lights-along-the-way

10 Comments

JJ – I give you 5 stars on this one. This was an eye-opener and you explained it so that many could clearly see the challenge. It raises a lot of questions. It would seem industrialization must ultimately give way to slave labor… hopefully in the form of relearning how to fend for our self, versus in service to the 1%. I’ve paused at the recent interest in encouraging the birth rate, while increasing the risk of jailing women who fail to carry to term. It would be easier to get rid of us, except then, who would do the work. In light of tariffs, I’ve been stocking kitchen oils, basic medicine and cleaning and baking chemicals – and cat food – enough to survive for a few weeks. The problem is clearly learning new ways to survive. I have to hold faith in the UNKNOWN and a power greater than our self. We hold the power to create solutions when we’re united for a common cause. The answer appears to be “stop, and change everything.” We have the faculties to figure it out. Education should be the highest priority, unless we all buy guns in preparation for a lawless society of resource marauders who kill to survive THE SHORT TERM. Since I was little I wanted to be here for the “end of the world.” We’re close to the end of the world as we know it. Seems like you could earn a PhD for this one. Love every moment of life that’s good and be grateful for it. I can’t bear the thought of those who are locked away and forced to survive in misery. God is the only answer to “impossible” that I know. My thoughts are turned to “come Jesus come.”

Debra, your feedback is very valuable, thank you! This is in many respects one of the most important articles I have completed as a lot (possibly most) of what is unfolding in the world on a material plane revolves around these issues (but it took time to put it all together). I’ve been a close follower of energy matters for more than 10 years by now and have included as concisely as possible all I have learned while making it as accessible as possible. The idea was that anyone who read this text and pay attention to the visualisations should be up to speed with energy matters with a clear understanding of the most important points without having to do all the research themselves (while the references are available should they want to). Your comment confirms that I succeed, so I’m very happy.

Peak oil is a topic many people avoid, consider a taboo, are in denial about, or don’t understand, but it’s a key factor in unfolding geopolitics today. Having this piece of the puzzle makes it easier to understand many other things too in relation to the cyclic shift/s we are undergoing: I will elaborate further on that in the next chapter, which should be published by end of July*.

Although we are at peak oil, the overall decline will be gradual at first, so I think there will be ample time for prepping, but getting into the right mindset early (which you are already in) makes us much more proactive and resilient. Everything you say in terms of having to fend for ourselves, slave labor happening in some places, learning survival skills and so on, will all become reality over time in many locations, in some places faster (and more so) than in others. This is already happening in parts of the world especially where conflicts have flared up and where they are spreading.

I think on a certain level many of us who are spiritual have always known that these times would arrive one day, but we were not always sure it would be in our lifetimes. I like to think of it as a privilege to have been born into one of the most important transitions that the human race has ever undergone. Future historians will conside it as one of the most important historcial times to learn from. Viewing it from this perspective helps me with keeping a positive attitude (we can help future historians by recording what’s unfolding in the present time).

Being stocked-up on essentials for a few weeks is very good practice in my view in case of a sudden financial meltdown (like what happened in 2008 – in Greece people could not get cash from ATM’s for some days, so be sure to have some of that stashed too …) or unexpected large scale unrest, or supply chain disrruptions, lock-downs, etc. Such events would become increasingly possible, including marauders and looters who won’t think twice … (this has already been happening on a low level in rural areas in South Africa for years).

As you say, people will be drawn together during these challenging times and communities will be strengthened. In the process we are likely to have deepening relationships with likeminded people (especially those we have to depend on near us for security and sustenance) through adversity. These are all positives, notwithstanding the difficulties we will have to face. The dessert of atomization that the modern industrialized world has become is so empty and devoid of real care for each other that a reset through adversity will certainly sort the wheat from the chaff.

Ultimately everything happening is Divine through the Divine Cycles of Time and the Universal Source ordering (arranging) it. I agree that we are close to the end of the world as we know it. I think many people can feel it, so there’s less scepticism about it by now. Whether it’s the actual Biblical end times is unknown – the Bible says nobody would know for sure, so we can’t/should not express certainty about it (although knowing it’s a possibility is important). In light of this possibility I believe we should prepare ourselves spiritually as best as we can according to the methods we know best for us personally.

Yes! Let’s love very moment of life and express regular inner gratitude for all we have now and have received in the past and will receive in the future by the Grace of God. Thank you very much for sharing your thoughts and for contributing them to this discussion, Debra.

*Edit/update: The next chapter is likely to be published by end of August, but possibly sooner.

Al Gore’s “An Inconvenient Truth” came to mind when I was reading it. It’s truth we don’t want to see, but have to face if we hope to survive… better sooner than later. And yes, you succeeded in making it clear for someone who knew next to nothing about the big picture. Thank you for your contribution. much love, in lak’ech, Debra

FYI – I’ve linked the post in the sidebar at jaguarspirit.com.

Thanks Debra – Much Appreciated.

Jean-Jacques

Brilliant essay, Jean-Jaques. You bring the spotlight on an underlying shift in global politics and business; a frightening view of what lies ahead, and such an important topic you’ve covered – and covered so well. I’ve heard for such a long time that the world would one day face resource limits, but with all the chatter that counts as “real news” these days, it’s easy to disregard something as life-altering as peak oil with all other pieces of information. This sheds a much-needed light on the topic.

A return to the natural order is indeed a sobering reality: the world has entered the end of an era. One that the modern world is ill-equipped to deal with. Based on the mindset of big business and big politics, this changing paradigm will hit, and hit hard. The number of people, especially people in power who are conscious of this situation, the global environment is so small, that it seems the shift to self-sufficiency is far from where we need to be. I appreciate how you conclude your post: ‘Returning to an authentic environmental consciousness.” Developing and prioritising spiritual growth strategies for psychological resilience.” Forward-thinking, honest thinking is how we can begin to address this situation. Again, well done, JJ.

Randall, thanks a million for your kind words. Very well summed up in your first paragraph. People’s attention is scattered and torn between so many topics with so many things happening in the world all at the same time in different places, that not being aware of something that everyone should be aware of (more than anything else probably) can easily happen. It’s also true that a lot of people are just not into this topic and have written peak-oil off as a conspiracy theory they believe has been debunked years ago.

This is one of the reasons why it was hard to write this essay because I knew that many people would probably simply ignore it, for reasons mentioned. Nevertheless I knew I HAD TO write it (and write it well) with sufficient references to backup my conclusions. Over at Substack I had tried to inform people during last year and had quite a lot of push-back with some people rejecting the notion of peak-oil out of hand, while others were under the impression that even if there’s peak-oil, abiotic oil would replace it. Many people have a tendency to view everything through conspiratorial lenses which undermines their critical thinking skills I would say in terms of weighing things up very carefully, because not everything is a “total conspiracy”.

I just wish I could write these essays faster because I have at least two more lined up moving more into the spiritual realms (and prophecy) next … We are indeed entering one of the most significant time periods known to humanity and as unstable as things are, we are also incredibly lucky to be alive right now, but it’s very important for us to pay attention to what’s going on on a number of levels.

I will elaborate further on the nature of the natural order we could expect how we are able to assist its birth in mind, spirit and action! As the Maya spiritual guide Carlos Barrios used to say, “Action (!) is the spirituality of our time” (rather than just meditating which can sometimes be a form of escapism or just endlessly talking about issues, which is a form of procrastination). With action in our personal lives we can constructively plan for the future.

More soon! Wishing you the best Randall and looking forward to reading about your next journey.

All the best,

Jean-Jacques

(PS: I still have a delayed post of Cambodia [last October’s visit] which I’ll publish at some point. Peak-oil has delayed it 😉 )

Dear friends, I believe that some of you have had difficulties to comment. It seems there was a problem with a Jetpack setting that deactivated the comment button. I have reverted to the classic WP comment form and I recommend logging into WordPress.com/Gravater before commenting. Please save your comment/s just in case and post it over at https://gypsycafe.wordpress.com/ should you encounter any problems here at Gypsycafe.org and I will resolve it by publishing it here.

My apologies for the technical problems!

Best wishes,

Jean-Jacques

Pingback: Beyond Apocalypse (Part 1) - Mimetic Rivalry in the Tower of Babel | Gypsy Café

Pingback: (1) Mimetic Rivalry in the Tower of Babel – Energy Shifts